John Muir’s Wilderness Essays

Read with a freshness that belies the generations that separate us from him, and with an urgency he never intended: the all-but unspoiled wilderness he loved is now being spoiled.

By Steven John

Reading this trim volume of John Muir’s collected essays brings you not only into the mind of the man who started the conservation movement as we know it, but into the world he so deeply loved. In Wilderness Essays you will be moved into the world the author inhabited, finding yourself deposited in a space as fully as you have when reading with the finest authors out there, both in fiction, nonfiction, or memoir.

And indeed “Wilderness Essays” is largely memoir, but today it reads as more than that: it reads as an admonition to give the wilderness Muir so deeply loved a chance.

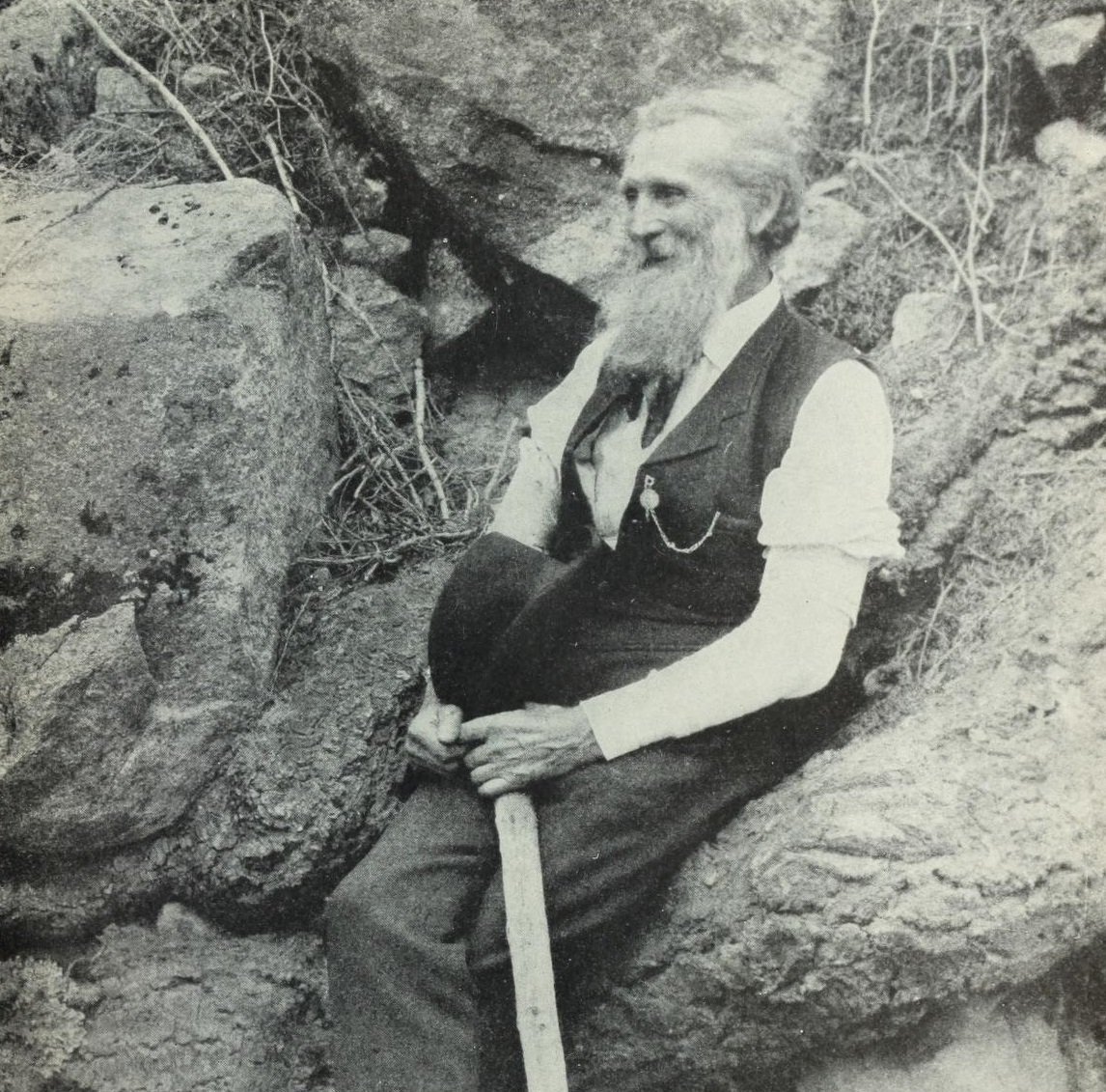

The awesomeness of John Muir – and I use that adjective in its traditional sense, the man is awe-inspiring – is all the more impressive because the man so little sought to be perceived as awesome. Or great or wise or even interesting; John Muir simply loved the wilderness, and especially the wilderness of the American West, this Scotsman’s adoptive homeland.

If you want to read a biography of Muir, then by all mean, you should. I recommend Son of the Wilderness by Linnie Marsh Wolfe. That’s not what we’re doing today, though – today, we’re taking a short look at a medium-length book that belongs on the bookshelf of anyone who shares a love for the outdoors, especially for those mountainous regions near the Pacific. Specifically, of course, I mean the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the place in which Muir was happiest, and one of the places (well, places, the Sierras being some 250 miles north to south and an average of 65 miles wide) largely preserved largely because of Muir’s work and his legacy.

But, with great restraint, I’ll not digress, happy as I am to bray on about Muir and mountains, those in particular. Alright, one digression: I’ve climbed and hiked about among Sierra Nevada peaks in deep snow, on days so hot I was in a t-shirt at 14,500 feet, and everything in between, I’ve seen the trees bare of leaves or the meadows in full bloom, and in all seasons, the Sierra are majestic and near to magical. I can only imagine them in their prime.

And really, that’s not a digression, for in Wilderness Essays, you get to experience the wilderness in its prime through Muir’s easy language and his infectious love for the outdoors. Not counting an introduction by Frank Buske, the book consists of 10 essays, some of which are more than 35 pages long, some shorter than 10, and about half of which center on the Sierra Nevada.

The way Muir wrote was the way one talks when three factors are present: first, the speaker knows the subject through and through. Second, the speaker knows his or her audience is genuinely interested. And third, there’s no rush, but also no need to use more words than needed.

Which is to say he writes in rich detail but without being lavish or loquacious, he assumes a bit of knowledge on the part of his reader, and he gives each aspect of his subject matter as much times and attention as it needs. Those with a true love for the outdoors will love, for example, the detail and description Muir uses in describing the snowfall in the Sierras throughout the year in his essay “The Snow.” Example? “The first heavy fall is usually from about two to four feet in depth. Then, with intervals of splendid sunshine, storm succeeds storm, heaping snow on snow, until thirty to fifty feet has fallen.”

Or take how he talks of the great tempest (and that word is used in the positive sense – Muir loved storms) he experienced farther east as written of in “A Great Storm In Utah”: “While we were reveling in this rare, ungarish grandeur, turning from range to range, studying the darkening sky and listening to the still small voices of the flowers at our feet, some of the denser clouds came down, crowning and wreathing the highest peaks and dropping long gray fringes whose smooth linear structure showed that snow was beginning to fall.”

In other words, it’s not “dude, you had to be there,” it’s more like… you’re there.

Long story short, if you don’t love the wilderness and you don’t love reading, then don’t read this book. Don’t bother. If you do love the outdoors and the written word, then by all means get a copy. You won’t read it cover to cover – and you shouldn’t, that’s not the point – but you will be hard pressed to find a better book of the wilderness for picking at when you have a bit of free time for a bit of vicarious adventuring.