“a few places I got an opportunity and a privilege to go to were blank on the map.”

Rick Ridgeway, Explorer, Climber, Conservationist, Dad

Rick Ridgeway Talks Mountaineering, Conservation, Family, and Knowing When to Turn Back, Even When the Summit

Is One Pitch Away

by Steven John

Rick Ridgeway was introduced to me as “the Real Indiana Jones.” 72 years old at the time of this writing, he’s a man with more accomplishments in the outdoor adventuring space than most of us could log in 144 years.

And then some.

But within just the first few minutes of talking to him, I realized this was an entirely inaccurate way to frame Rick. Not because he hadn’t lived a life of adventure, achievement, and discovery, much like the fictional Dr. Jones, but because Ridgeway defines himself equally by his accomplishments in the field as he does by having been a steadfast and caring husband and dad.

In fact, just a little while into our interview, I asked Rick: “All right, you've just written a memoir, [Life Lived Wild], so clearly you're in a reflective phase of life. Looking back, if you had to choose just a few words – let's say three – that define you, what would those be? Whether it's climber, mountaineer, or conservationist?”

Without a moment’s pause, Rick Ridgeway answered: “Well, [of] those things, two of those that you mentioned, I’d say mountaineer and conservationist, and family man too, that's up there.”

He could have said adventurer, author, documentarian, multi-time first ascender, and on the list goes, but he filled out his self-description with “family man.” As you’ll come to see, that speaks to the balance Ridgeway has always managed to find in life, a balance that has let him accomplish much – including those first ascents, the exploration of completely uncharted land, contact with remote peoples, stewardship of endangered species, and on the list goes – and yet still be present for loved ones. Which you can take to mean two things: first, making time for other people in life, and second knowing when the risk simply outweighed the reward. We’ll get back to that.

Pushed to expand slightly on self-definition, he settled upon one more term. “Let's pick explorer. That more comprehensively captures my interest in mountaineering, but also in other outdoor sports that I did, including river rafting, and I think just getting into some of the last wild places on our planet would be under that rubric.”

“And I feel privileged to have lived through a time when there were still places in the world that were off the map. I mean, literally, a few places I got a chance and an opportunity and a privilege to go to were in areas where on the printed maps, pre-digital era, they were kind of blank on the map. Literally, there were sections where it would say: ‘Geographic data incomplete’ and: ‘Cardiographic information uncertain.’”

“Those kinds of things. And that was pretty cool to be able to still live in a time when those kinds of places on the planet existed and that really motivated me. Since I was a kid, unknown places in really remote regions of our world always fascinated me. So again, I used that word privilege to describe the opportunity I had to go to a few of those places in my life.”

A few places Ridgeway has visited, both on and off the map, include the 28,251-foot-high summit of K2 – he and his team were the third group of climbers and the first Americans to summit this second tallest peak on earth – the Tibetan Plateau, the Amazon Rainforest (hiked through to reach a climbing spot, of course), Antarctica, and plenty of Andean peaks, often climbed with his good friend, famed climber and founder of Patagonia, Yvon Chouinard.

In the course of his adventures – those on and off the map – Ridgeway logged multiple first ascents, charted new passages across unexplored lands, spent weeks and sometimes months living off the grid, and more than once he faced life-or-death situations. (In fact, more than twice. Or thrice. Or four times.)

I asked Ridgeway how he had managed to defy that bittersweet aphorism: “There are old climbers and there are bold climbers, but there are no old bold climbers.” His response was refreshingly clear-eyed and only slightly tinged by regret.

“Well, I knew when to turn back.”

“And, of course, that's the answer that any old mountaineer who lived a quasi-bold life might say,” Ridgeway added. “One of the hardest, and one that I still ask myself if it was the right call, was when I was in my early twenties. With some other guys, I was trying the first ascent of the east ridge of Huantsán in the Cordillera Blanca in Peru. And it was one of the great ridge climbs of the Andes, maybe right up there in the very top. And we tried it Alpine style, and one by one, the other guys dropped off until finally there were just two of us left. And just on the summit headwall, I got up into a section of water ice that was fairly steep and it was a couple of pitches long, and we didn't have any anchors left, no ice screws, nothing, we were out of gear.”

“And I felt I could get up and down on my own, but I didn't think the guy I was with could pull it off, so I was going to have to ask him to unrope and I didn't want to do that, I didn't want to almost abandon him. He'd have to try to climb down on his own or wait for me. I turned around, and I still don't know if I made the right decision, but it would've been kind of sketchy because I hadn't done much ice climbing back in those days. There I was just below the summit of what would've been one of the coolest first ascents in my life, so I think about that. But I don't regret having turned around, I just wonder, whether I could have made it or not.”

Boldness tempered by reason is exactly why Ridgeway is today in a position to have penned a memoir, enjoyed a four-decade marriage (his wife passed a few years back, but he remembers her with joy, not heaviness), raised children who have since raised children, and also to have given so much of his life to pursuits beyond bagging another summit.

For as rightly proud as Rick Ridgeway is of his accomplishments ascending rock and ice, it is his conservation work he feels has meant the most; it doesn’t hurt that much of that work brought with it plenty of adventure.

Asked point blank: “What do you consider your greatest accomplishment?” Ridgeway replied: “Well, in mountaineering, it's that third ascent of K2, that climb took more tenacity and just stick-to-itiveness than anything else I did. But in terms of the most satisfying and gratifying adventure that I went on, it would have been the traverse of the Northwestern corner of the Chang Tang Plateau, when with some of my mountaineering buddies, we were following the migration of an endangered antelope – the Tibetan antelope, otherwise known as the chiru – to try and discover their calving grounds so that we could bring a global attention to the plight of those animals who were being poached and safeguard their calving grounds before the poachers could get there.”

“And it worked! We pulled it off and we got a new protected area created and the animals are, even today, still on an upward path doing better than they were before our trip. And it wasn't that we alone were responsible for reversing the plight of the animals, but we added to a global effort to save them that worked and that was just deeply satisfying. It meant so much more to use our mountaineering skills, being able to traverse a super remote place on foot without support, in the safeguarding of an animal, instead of just some self-directed goal of getting ourselves to the summit of some mountain.”

Not that summiting some mountain isn’t a pretty great thing to do. And in fact, if you yourself aim to do that, or just to gain some elevation (no summiting needed for a good time) or go for a long through-hike or a short day hike or whatnot, chances are decent that Ridgeway’s work will play a role in how you do it. For during the course of his long career, his experiences and insights would directly contribute to the design elements of multiple types of outdoor gear and apparel.

Asked about any of the gear he had come to rely upon out there in the field – or any hardware that had ever failed him – a smile colored Rick Ridgeway’s tone. “Yeah. Yeah, I got a good one for you. When we went to K2 in 1978, Nike was one of many sponsors, and in addition to some super important cash, they gave us training shoes that they had just designed, they were called LDVs and it was like one of the very first track and field training shoes ever made. So some of us wore them as trekking shoes [while headed] into base camp. And back then it was 110-mile walk, 220 miles round trip, and we wore these training shoes in and out and by the time we got out, they were more tape than shoe. But John Roskelley and I had kept notes about how they could be improved to make them into a lightweight, flexible, but durable trekking shoe. And Nike took those notes and they came out with a line of trekking shoes with fabric uppers – GORE-TEX fabric – that were flexible. And they incorporated our design notes and they were the first fabric upper trekking shoe anybody ever made and they were a big hit and they started a whole kind of subcategory of the shoe industry.”

“And then those shoes, the three models that Nike released when they came out, they ran ads in the outdoor magazines with the picture of Roskelley and I at the base of K2 wearing these things full of holes and that little story was under there. So we were also in their first ad. One was called the Lava Dome. And the Approach and the third was called the Magma.”

So it’s not just the Tibetan chiru that can thank Rick Ridgeway, but anyone looking for some decent mountaineering gear, too. Beyond the gear, if you’re looking for guidance on how to get into adventuring, Ridgeway’s advice boils down to this: just go do it. But he added some nuance, too.

“My advice is to pick an adventure and a place to have an adventure that really increases the likelihood that you're going to enjoy yourself, that you're going to have a good time. And part of that good time is going to be finding pleasure in being in wilderness. I really recommend anybody to think about what their own particular interests are, what their skills are, what kind of place in the world they gravitate to, and pick something to do there. But if you're just starting out, don't pick something that has kind of a high possibility of being so uncomfortable you may not want to go back again. So get into it, stepwise like that, but get into it in a place where you can increase the likelihood of falling in love with the place and with nature, because that's going to provide the highest likelihood you're going to get hooked and that it's going to change you.”

“And then after you start, getting it into your soul, the beauty, the solace of the experiences – then those override the pain, which is going to be there if you keep doing it and you keep upping the challenge a little bit. Back in the day when I was starting out, we didn't even think about training, like nobody that I knew trained, we just went out and did it. So if you had a Himalayan climb coming up, well, you just tried to get out and do a few climbs before you went to the Himalayas. I didn't consider it training, I just considered it doing.”

While out there just doing, despite his caution, reason, and commitment to always make it home to his family, Rick was nonetheless confronted with dangers so great they called up those greatest questions in life. When I asked him about his greatest challenges in the field, he answered not with any specific ascent or traverse or exploration, but rather with the existential.

“I think the biggest challenges in my outdoor life were the times when I came really close to not coming home. And I had to, in some cases, not only dig deep to survive, but I had to reconcile my mortality in a really deep way and that was hard, it is hard for anybody to do that. But the rewards of having done that are immense. The value that reconciling your own mortality can bring to the way you live your life at sea level on a daily basis can be one of the most important things you can achieve in your life.”

And what had those moments of deepest navel gazing taught Ridgeway? That, within reason, getting out there is not only worth it, but almost essential. I asked Rick about a few of the places he felt anyone who could see should see, and again he eschewed the obvious (Everest, the South Pole, Iguazu, and so on), instead speaking of the uncharted.

“It should be a place that is still little visited and as wild as possible. I think it's really important, despite the fact that if everyone on the planet tried to get to the last remaining wild places, they wouldn't be wild anymore, despite that, that if someone can find the wherewithal to identify those places and get yourself there and get yourself there with enough time to absorb what true wildness feels like, to be there and be there quietly and be there reflectively and let that place get into your bones, then I advocate everyone should try to do that because you learn so many things. You learn about your place in wilderness much better when you're in true wildness. You learn how you fit into the web of life when you're out in wild nature, especially, untraveled wild nature. And learning those two things, you learn a lot more about yourself.”

Talking about places kept as wild as possible led Rick and I around again to the topic area second nearest and dearest to his heart – his family being #1, from his late wife to his kids to his grandkids – conservation, climate change, and what we can all do to help.

“How confident are you, if you are confident, that we humans can correct course, or perhaps better put it, right the ship and do better for this planet? I asked Rick. And to be honest, I rather expected a man of his age and experience, a guy who has seen much of the world that is most impacted by human activity, those high-altitude places, those formerly wild places, an explorer who has seen how much of it has changed, well, I expected his answer to be jaded, if not outright jaundiced.

But it was quite the opposite.

Rick Ridgeway remains confident that we can right the proverbial ship; that we humans, the cause of global climate change, can yet work to fix things. If only we try.

“We have all the tools in our box now to solve climate change,” Ridgeway said. “And I am on the teeter-totter about whether we're actually going to use those tools in time to prevent humanity from collectively going over the cliff. But we’ve got a good shot at it, and I work hard at trying to increase awareness of what those tools are. I work with groups that have shown through the best science that anybody's done yet that scaling the conversion of fossil fuel to renewable energy and scaling the protection of nature through increasing protected areas, as carbon sinks, and converting the production of food and fiber from industrial practices to regenerative protocols, that if we scale those three things – and we know how to do it, we know how to do all those things, the technology's right in front of us – we don't need anything new, we just need to scale what we already know how to do. And we can keep the planet to 1.5 degrees [Celsius temperature rise] doing those three things without even having to significantly reduce our own consumption, although, that's probably going to be required at some point as well. But we can do this and we know how to do it and science has proven now that we can keep to the plan, to 1.5 degrees, it's not that hard to do, it's not a sacrifice. In fact, I think doing those things I just mentioned, and reducing our consumption some, can still allow us to live complete, fulfilling lives. And I would argue that they're even more complete and fulfilling doing those things than the ways in which most of us go about our present day lives now.”

We can all hope he’s right, and just maybe he is, for after all, Ridgeway he has lived a complete and fulfilling life largely filled with learning about the issues of climate change, habitat loss, and other entirely manmade catastrophes. If he can remain confident at 72, with long perspective and profound experience to bolster it, why not?

And more to the point, we can do more than hope. Sure, Rick Ridgeway just released Life Lived Wild, but his memoir is hardly his swan song. He still bags summits in his eighth decade on earth, he’s got those grandkids to tend to, and he’s still actively engaged in working to better our world. Rick is the chairman of One Earth, former VP of Public Engagement for Patagonia, and a tireless advocate for humans to all be their best when it comes to caring for our shared home.

Near the end of our conversation, I asked Rick for a few everyday tips that could help out, and he was effusive there as he was when talking about first ascents.

“The tropes are, of course, things like recycling and driving an electric car and those things, and we all need to do that, but we need to do more than that,” Ridgeway said. “And I think disciplining ourselves to reduce our personal consumption is a good idea, but I also think supporting the groups, whether with volunteer work or with philanthropic contributions, who are doing the groundwork towards climate change solutions is probably even more important than those other personal shifts in our habits.”

So listen, yes, go find your wild, go climb a mountain, go do it all. But in the meantime, remember that you’re right there on the same planet whether on the last pitch below the summit or simply sorting through your garbage properly. The former will do much for your soul and psyche; the latter will help us all out a bit.

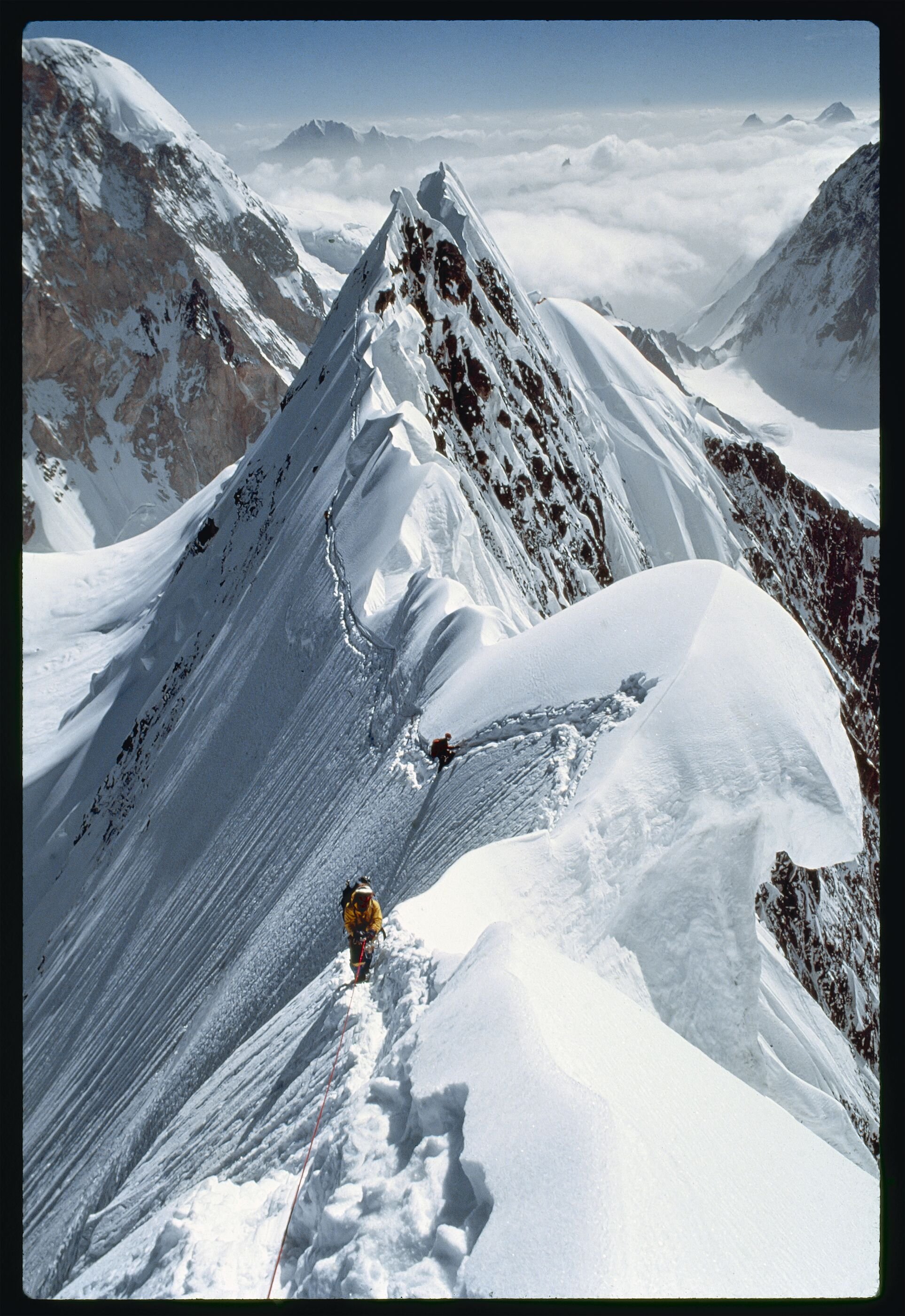

Photos provided c/o Patagonia BooksRick Ridgeway Headshot - Photo Credit: Jimmy ChinBanner Image: Summit of K2, 1978 - Photo Credit: John RoskelleyLeft to right, first group: Northeast Ridge, K2 - Photo Credit: John Roskelley; Antarctic Rock Wall - Photo Credit: Gordon Wiltsie; Icefall Traverse - Photo Credit: Johan ReinhardNike Shoe Ad c/o Rick Ridgeway/InstagramLeft to right, second group: Patagonia, Chile - Photo Credit: Jimmy Chin; With the Dalai Lama - Photo Credit: Rebecca Hale/Nat Geo; Chang Tang Plateau - Photo Credit: Jimmy Chin