Dylan Tomine

Fisherman, Family man, Writer

by Steven John

If you were to ask Dylan Tomine to describe himself in just three words, it’s a safe bet the words he would choose are fisherman, family man, and writer.

Granted, that’s four words, but you get the point: Tomine’s life has been defined by an enduring love of the outdoors and especially by time spent on or in rivers, lakes, or the sea – so much so that he has written a book called Headwaters: The Adventures, Obsession, and Evolution of a Fly Fisherman.

Likewise, much of his life has been shaped by sharing that passion for the outdoors with his children, both now young adults, with whom he has plied the backwoods, raised gardens from the ground, trekked many a mile of trail, and of course caught a lot of fish. His devotion to sharing a love of nature with his loved ones was the inspiration behind his earlier book Closer to the Ground: An Outdoor Family’s Year on the Water, in the Woods, and at the Table.

That subtitle of his first book alone was evidence enough for me to suspect Dylan Tomine might be a good person for a Dad Gear Review chat. So I set up a meeting (remotely, because of pandemics and thousands of miles and such) at the start of which I said to Dylan: “We’ll keep this chat to 10, 15 minutes at most, if that works for you.”

Dylan graciously made clear he’d be happy to chat longer if need be. About 40 minutes later, my suspicions thoroughly confirmed, I wrapped up a conversation with a person who is about as “Dad Gear” as it gets, if you’ll allow our own publication’s name to be used as shorthand.

What do I mean by that? Dylan Tomine is a father (and a person) for whom living a life connected to nature is essential; without the natural world as a frequent, almost daily touchstone in his life, he would feel wayward, unfulfilled, reined in, and on it goes. But make no mistake, he is hardly an ascetic or an off-the-grid survivalist type – “I'm not a sustainability zealot in any way, shape or form,” he told me, adding: “I use paper towels with the best them!”

Rather than living a life defined solely by the wilderness, he lives a life informed, inspired, and regularly revived by it, and by regularly exposing his family to the natural world yet without imposing a lifestyle on them, he has raised kids who love and respect the earth but also very much live in society. And if that’s not a laudable achievement for the Tomine gang and a goal for the rest of us, I’m not sure what is.

Photo by Mauro Mazzo

Photo by Tim Pask

Photo by Danielle Dorsch

With that goal in mind at all times when thinking about the Dad Gear of it all, I led off the more formal interview part of my talk with Dylan Tomine with a decidedly broad question:

Why is it important to get kids out into nature?

“Wow, that is a big one to start with!” Tomine replied with a laugh. Then he answered with nothing less than an off-the-cuff mini dissertation.

“I think for whatever [number] of millennia, kids and adults have grown up as part of nature, right? We're genetically hardwired as animals, as critters, to be part of the natural process, and I think the way we live now – and it's been noted by a lot of people – the way we live currently, I would say mostly over the last 50 to 100 years, is largely removed from natural processes. From [knowing] where food comes from or just breathing fresh air and being outside and poking around and trying to catch a fish or find mushrooms or all the things that were normal parts of our lives for so long, these things have kind of disappeared from our daily lives.”

Continuing his answer to the “why should kids get out there” of it all, Tomine briefly tacked away from the existential, saying: “I mean the number one reason for me [to get outdoors with kids] is it's fun. It's fun for the kids and it's fun for the parents,” but soon he was back in deeper territory.

“It also sort of taps into what I think of as deep rooted genetic instincts that are important. Being outdoors, for kids, promotes decision making in a different way in that if you are a kid and you're going to look for mushrooms or you're trying to dig clams or catch a fish or whatever, you have to absorb the conditions, which I think kids do somewhat intuitively – with some instruction from adults – but you have to absorb the conditions and then figure out how to make those decisions.

“Do I go upstream or downstream? Do I go north or south? Can I make it back home before dinner time if I'm wandering off? And all those sort of things. I think it all goes back to our heritage or our genetic hard wiring that are just important parts of thousands of years of human experience that we just don't have very much of anymore.”

All true, the lost instincts and the fun of it both. So… how best to start a recovery of the fun and the nature-human connection? Just start getting the family out there, of course. But done right, for as I have noted many a time in my own life (and as we have noted in other Dad Gear Review writings and during conversations with other outdoor dads), a bad campout, paddling trip, or even an unpleasant day hike can quickly sour kids on the wonders of the natural world. Naturally, then, I next asked Dylan Tomine: “As you're planning an outing, what are a few of the tips you have to make that wilderness family adventure a success?”

“Lots of food,” Tomine replies at once, no need to think about it, adding: “Nothing makes kids unhappier than being hungry. And also, nothing makes it more fun than having little treats and snacks along the way.

“So I think that food would be my number one thing, and then the second thing to me is that the kids are outfitted in gear that's equivalent to what the adults are outfitted in. I mean, I was digging clams one time out on the coast with a buddy of mine, and it was pouring down rain and blowing sideways – this was actually before I had kids, but was how I started to learn this – and there were a number of parents there that had full commercial fishing-grade weatherized clothing on while their kids had on trash bags with holes torn out of them! That’s what they were wearing, and the kids were miserable. And I pretty much could guarantee that those kids never wanted to go clam digging again because of being wet and cold. And so I think it's pretty important to make sure that your kids have the gear that will keep them comfortable.”

A sentiment with which I could hardly agree more and that we even espouse ourselves time and time again: just because your kids are kids, you can’t ply them with inferior gear. It’s a surefire recipe for less enjoyment of the experience and, further, it’s a potential recipe for discomfort or even for injury. Yes, they outgrow gear and apparel and there’s an expense there, but in the cost-benefit analysis, their safety and enjoyment just have to win out.

Photo by Dylan Tomine

Now, assuming the kids are properly kitted out, what are some ways to better ensure the enjoyment part? I flipped the equation a bit and asked Dylan for tips on things to avoid when one plans a family outing.

“I think, I mean the biggest surprise to me, which I wrote about in Closer to the Ground, is that, well everybody told me: ‘Oh, if you want your kids to like fishing, then you got to make sure that you catch tons of fish so they don't get bored!’ And what I actually found out with my kids [was] that really just the act of going out and doing something with their dad was what they really liked and it was okay if we weren't catching fish every two minutes. Myself? I'm a pretty goal-oriented, kind of competitive and driven person. But I try to avoid transferring that definition of success, like the adult definition of success, onto the kids.

“So I would try to avoid having really specific goals and ideas of what makes for a good day, and let the kids direct what success is. There were so many times where I was like: ‘Hey, we’ve got to hurry. We're going to miss the tide!’ Or: ‘The conditions are perfect; we have to go right now!’ And I would be frustrated because the kids would be looking at caterpillars on a leaf or wanting to look at the little crabs at the boat ramp or whatever it was. And it was a hard lesson for me to learn that really, if that's what they're interested in, it's important that you don't put your own ideas of what success is onto them.”

Of course, even with that gentle approach of guiding kids to nature without specific expectations, the approach has to be malleable as kids get older. So I asked Dylan: “How can you keep kids engaged with nature as they get older and their interests change?”

“It's difficult,” Tomine replies. “My kids are like every other kid: they're glued to their phones. They’re busy. Both my kids have been pretty involved with travel sports, like kind of high level athletics – my daughter's a volleyball player and my son plays basketball – and I think at some point it occurred to me that when they were small, if we wanted to spend time together, we did what I wanted to do, and they came along. I think for adults, for parents, it's really helpful to think – and this wasn't easy for me to figure out, it's an evolving situation for me — but it’s helpful to have the realization that now that they have some of their own interests, if we want to spend time to get other, the trade off from earlier is that now I do what the kids want to do. And if that's going to basketball tournaments or volleyball tournaments, I need to be happy to do that, to spend the time with them, for kind of the tradeoff. What happens, if you're willing to do that, is that as the kids get older and start to look back and see the value in the earlier things that you did and the times [shared], when the schedules line up, they still want to go fish or dig clams or something with their old man, but it's definitely harder.”

Now let’s assume the schedules have lined up and the shared interest in some outdoor fun is there but… you really don’t want to spend a lot of money. I figured it would be a good idea to ask a guy with decades of experience out there, and the cash outlays that go with it, the following: “How best can people enjoy nature without spending a lot of money and without necessarily traveling very far from home?”

“Yeah,” he replied, nodding. “I think that's a really good question and I think especially after we just talked about technical gear for kids, which is not cheap and they do outgrow it and that sort of thing, but I think there's so much to do that’s [affordable]. There can be so many small adventures close to home. It depends where you live of course. If you live in Manhattan, it takes a little more doing to get out of the city – but then there's a lot of cool foraging opportunities in Central Park. So I think for me, it's sort of trying to figure out what's close at hand. If you live in New York City, there is fishing to be done within the city limits. In almost any city, there may be fishing in a park pond or you might be looking for mushrooms in a city park or whatever those things are, and the value is still there. Then those short, close to home adventures, three, four hours away — or actually just a couple hours is probably a better idea for a fun time for younger kids.

“I don't think it needs to be: ‘Hey, we're gearing up for this expedition to climb K2.’ I think it's really just about saying: ‘Hey, let's go do this,’ and making it fun for the kids. And to me, if the kids are having fun, then the parents are having fun, right? I don't even care what the result is if the kids are enjoying it; even now with my kids being teenagers, that's exciting for me. And so I think that that's just kind of an attitude shift for of a lot of us. Before we had kids, we were pretty big time traveling adventurers. After, we found ourselves sort of just scaling down. And really doing those things with my kids forced me to learn a whole lot about what's nearby, because it was: ‘Well, that's what's here.’ And that's what's easy to do when they're younger because of cost and attention span.”

Photo by Danielle Dorsch

Photo by Dylan Tomine

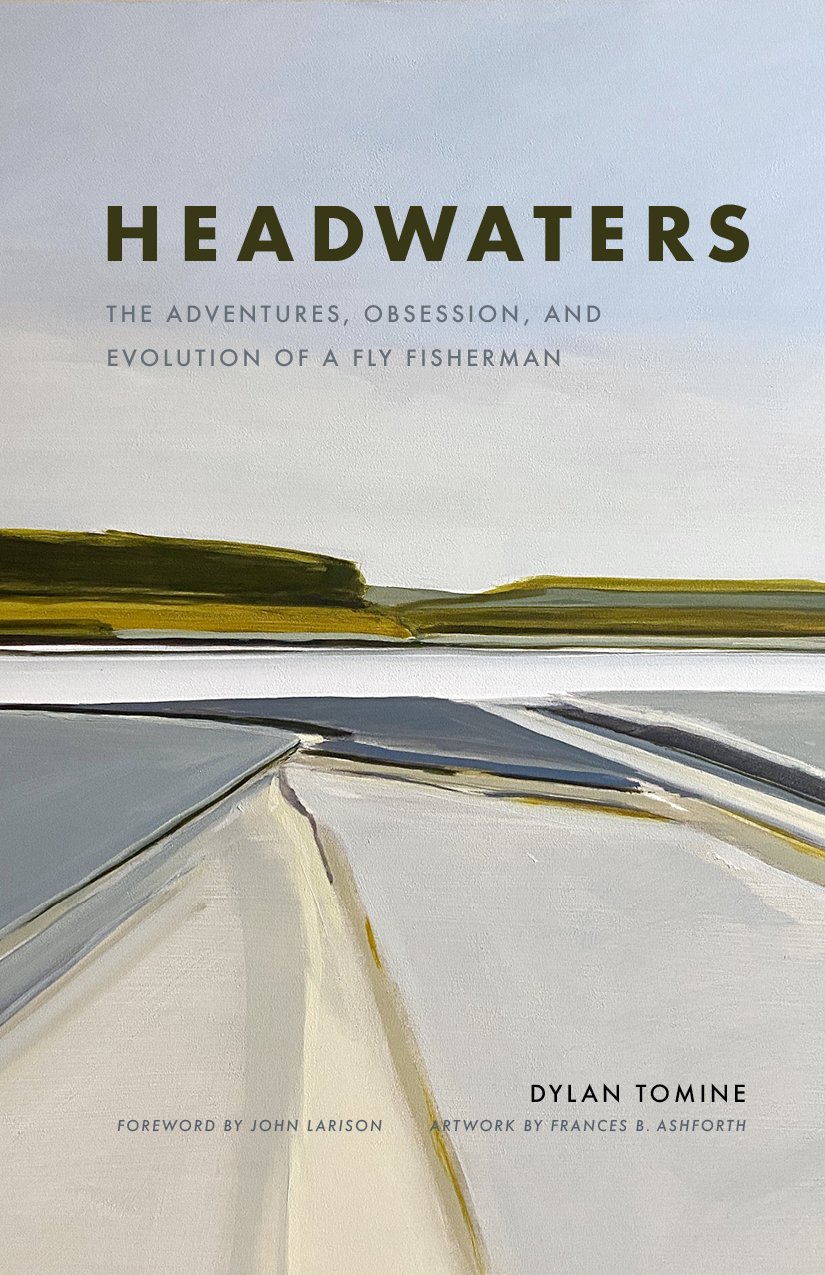

10 years after the first edition of Closer to the Ground was published his kids, now almost adults, definitely have longer attention spans. And their lives are often outside of his. Thus, with a bit more time on his hands given that the most of the hands-on work of parenting was in the proverbial bag, Tomine finally turned to writing a second book. Or rather to compiling and editing a lifetime of work, to be more accurate. When I asked him about the inspiration for his new book, Headwaters, Tomine explained it was a project long in the making.

“How Headwaters came about,” Tomine said, “was a process. It's a mix of previously published stories and unpublished stories. I'd been doing these readings and people would say: ‘Oh, where can I get that?’ Or: ‘Where's this story or that story?’ And the only answer would be: “Well, that was published eight years ago in this journal and it's hard to find.’ So I'd had in mind to do a collection all along, and then I think what occurred to me at some point [was] that if you look at the arc of somebody's writing career, if you look back at what you've written over time, you can sort of read between the lines and see an evolution of yourself as a writer and as a thinker and as a human being.

“In my case, my really early stories were 90% about travel and adventure and fun and catching fish. And my more recent writing was really 90% about either conservation issues or more kind of emotional thinking in more of an introspective kind of style. And so by arranging [the stories] in a chronological order and then holding them together with these little snippets of memoir, kind of like snapshots of my memories of fishing, I started to feel like it told this bigger story that it was sort of more about the evolution of an outdoor person.”

And there it is, an even better way to sum up the goal of it all, “all” meaning what we do here at Dad Gear Review, what Dylan Tomine does day in, day out (and with the occasional well deserved day off), and what so many outdoor-oriented moms and dads (and uncles and friends and teachers and so forth) are doing: we’re working on the evolution of an outdoor person, kids and selves very much included.

Photo by Weston Tomine

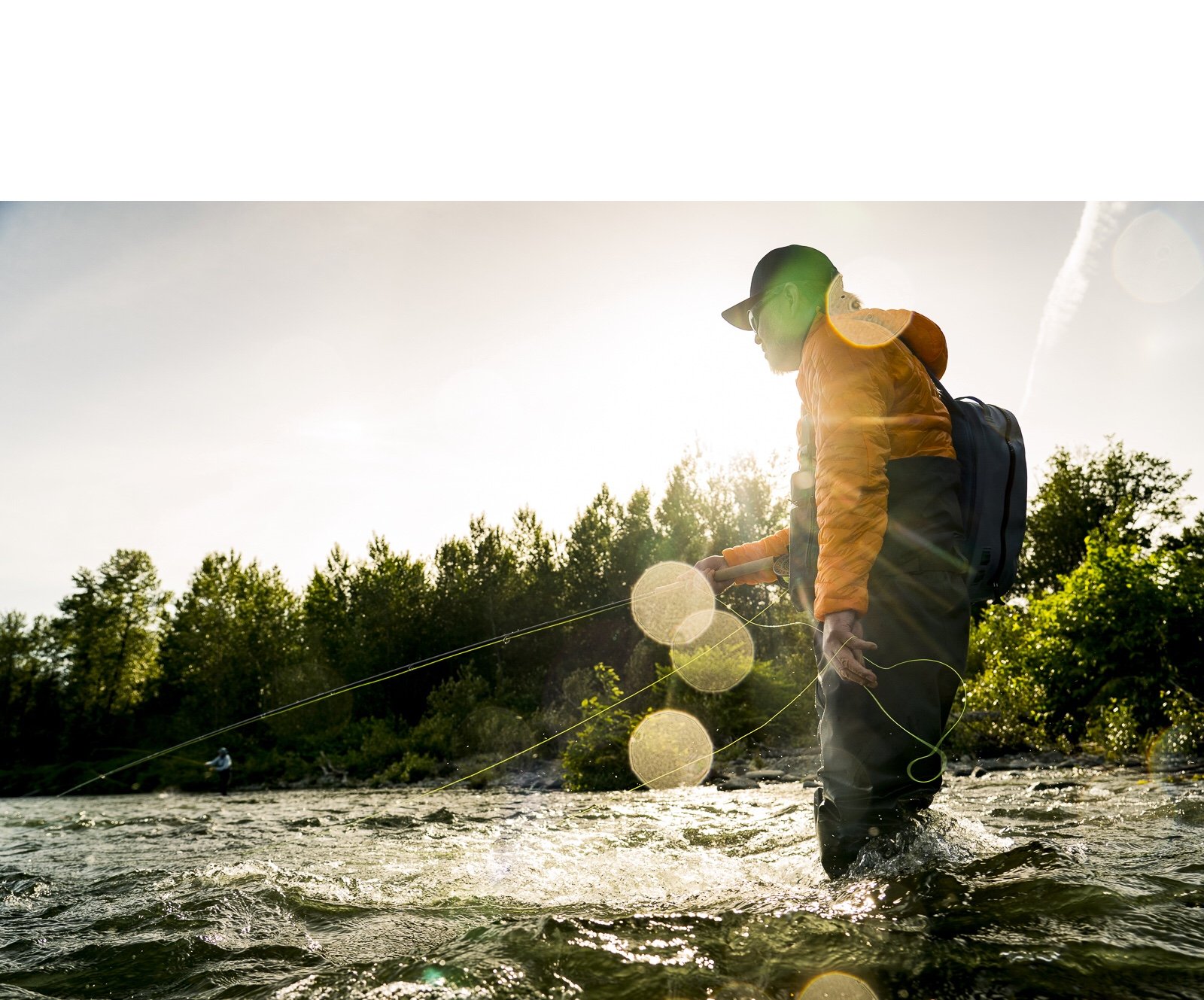

Banner image by Matthew DeLorme